In light of repeated incidents of anti-Asian hate in the United States, the Applied Economics Clinic reaffirms its statement on racial equity: AEC stands in solidarity with demands for racial justice, without which environmental and economic justice can never be achieved. In this regard, blog posts for this week will center the connection between environmental justice and Asian American communities.

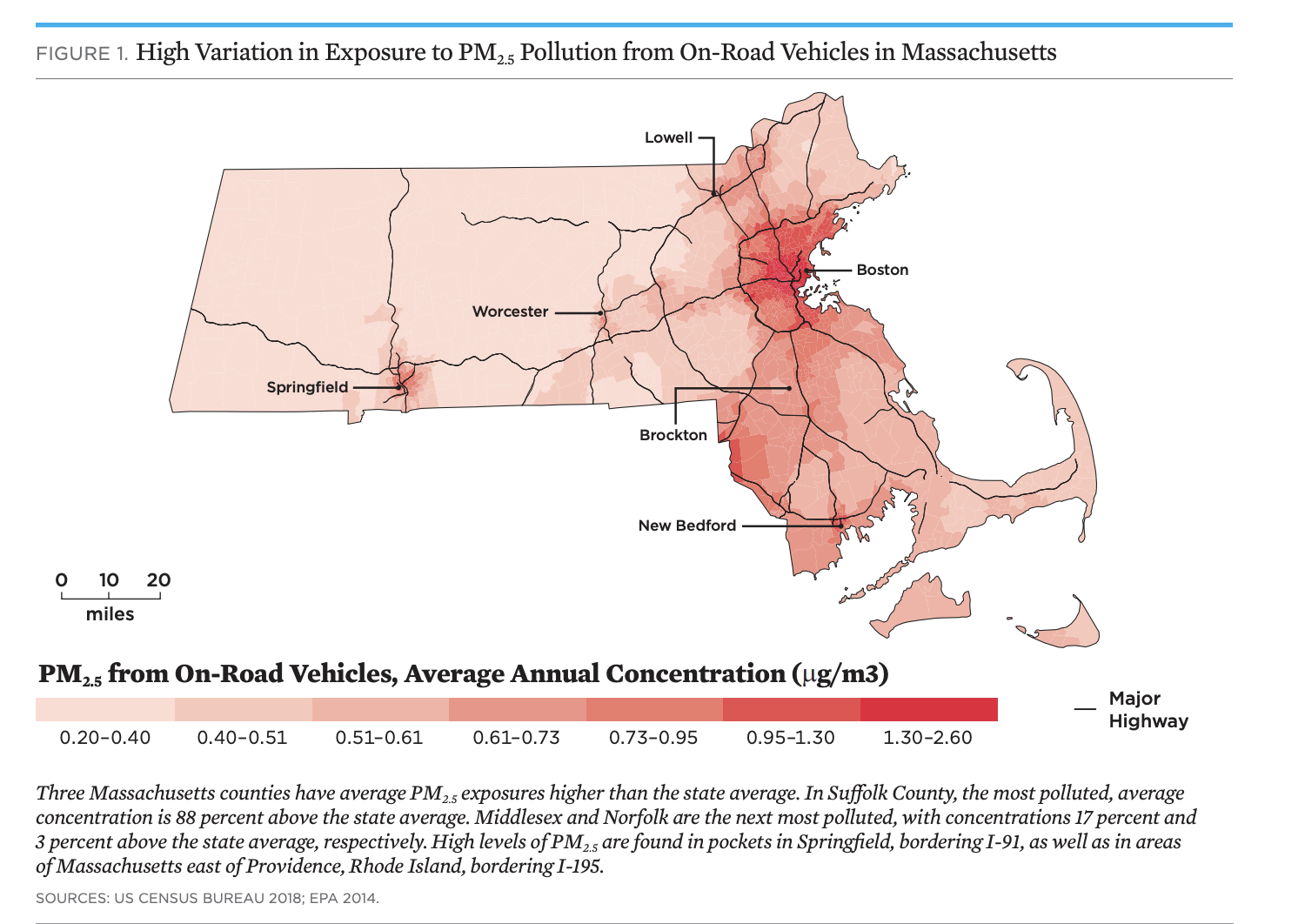

In 2019, a Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) analysis showed that Asian American residents in Massachusetts “are exposed to PM2.5 concentrations from on-road transportation that are, on average 36 percent higher than the exposure of white residents.” Annually, 3 to 4 million deaths are attributed to air pollution from fine particulate matter; PM2.5 by itself is estimated to account for 95 percent of the global public health impact from air pollution. Exposure is associated with health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, asthma, and slowed-lung function growth in children. In Massachusetts, worse air pollution is concentrated around downtown Boston, the I-93 and 95 corridors, and gateway cities such as Lowell. Boston’s Chinatown has the highest level of vehicle emissions of any neighborhood.

In light of the recent focus on the racism and violence faced by Asian Americans in particular, as well as the codification of environmental justice in Massachusetts’ new climate legislation, differences in air pollution by neighborhood is a timely issue. In 2017, researchers at the University of Texas, El Paso (UTEP) argued that the “model minority” label had resulted in too little focus on the environmental impacts faced by Asian Americans and that too few studies have disaggregated the damages of toxic exposure on Asian American subgroups. Studies that do are revealing. For instance, a 2010 study in Environmental Justice found that 40 percent of the Japanese population in the United States and 30 percent of the Filipino population in the United States live in counties that exceed PM2.5 air quality standards. The UTEP study also found that neighborhoods with higher proportions of Chinese, Korean, and South Asian residences have a higher risk of cancer “significantly greater cancer risk burdens relative to Whites” due to hazardous air pollutants compared to White residences.

When considering how to tackle this problem, there are two places Massachusetts could start. The Applied Economics Clinic (AEC) wrote a report recommending numerous metrics to evaluate various equity and justice impacts for the Massachusetts Climate Justice Working Group’s priorities. The recommendations included building air monitoring stations for environmental justice populations and other historically marginalized communities to ensure effective data collection. New monitoring stations should be paired with a hotspot declassification standard once pollution truly falls below “hotspot” levels. AEC’s recommendations also include proposals to effectively target investment in environmental justice populations.

The second way to tackle this disproportionate exposure to air pollution is the content of environmental investments. The UCS report specifically recommends electrifying bus fleets. If begun with school busses, the benefits on student health from reduced exposure to particulate matter would be notable. Communities will also need assistance in purchasing these busses. As shown by a Massachusetts pilot, they will need assistance managing the battery infrastructure necessary to ensure energy savings from electric school buses are not lost to uncontrolled charging or to so-called “vampire loads” to maintain battery temperature. Finally, technical assistance will be necessary to ensure these busses can match time spent on the road by their diesel counterparts. For Massachusetts itself and communities with large or rapidly growing Asian American populations, attention to this policy area is imperative. It is a clear and tangible area for advancement.