Reproduced from: Victor, D., F. Geels, and S. Sharpe. 2019. Accelerating the Low Carbon Transition: The case for stronger, more targeted and coordinated international action. Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Coordinatedactionreport.pdf. Pg. 14.

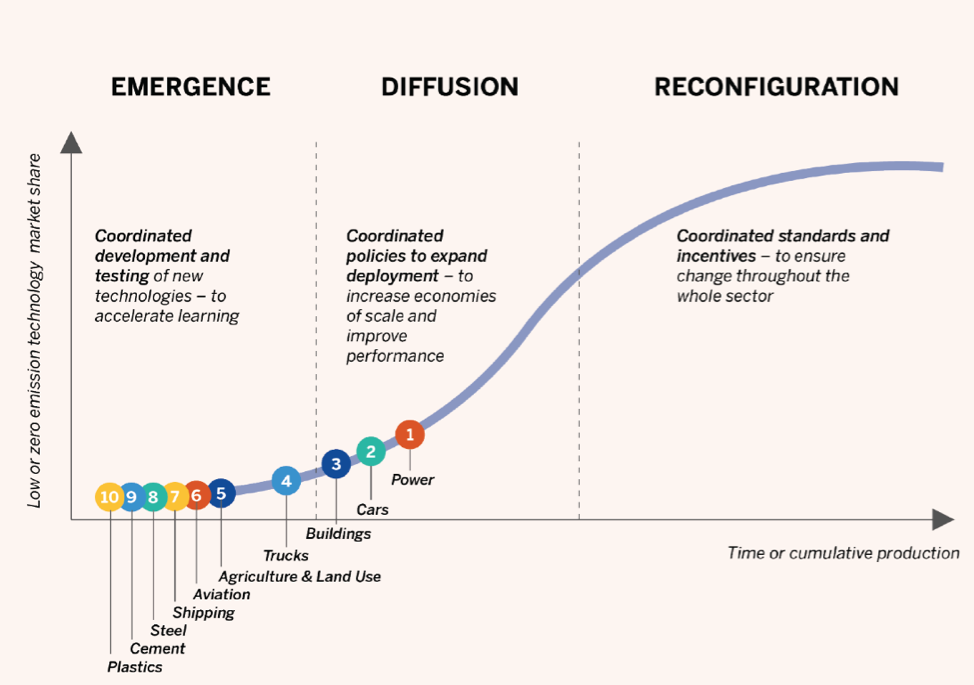

The Decarbonization S-Curve illustrates the pace at which zero emission technologies are adopted, which is neither smooth nor steady. Consequently, neither are emission reductions. The graph’s horizontal axis shows time, and the vertical axis indicates how widely used the technology becomes. Adoption is slow at first; the unproven technology struggles to find investors. As government investment, research and development spending, and other subsidies begin, adoption picks up as more firms invest to earn profits from selling the technology. Finally, the takeoff proceeds rapidly as new markets and industries develop, before slowing down as the market matures. It is in the takeoff stage at which the pace of emissions reduction is at its fastest. According to a study published in Research Policy on green technologies in Austria, the takeoff stage can only happen when politics and policy work effectively with the new technology.

In other words, the takeoff of emissions reduction from new technologies does not happen automatically and can be stopped. For example, administrative hurdles to connecting solar and storage projects to the electric grid could result in long waiting times. A shortage of charging stations or battery materials could hamper electric car purchases. According to a report by Brookings, to achieve ambitious emissions reductions governments must pursue R&D policies in the early stages, use capital grants and investment in the takeoff stage, and anchor the market with regulations and standards by the final stage—. If these problems are not addressed, we might find that progress towards our climate goals grinds to a halt. Just because emission reductions can be quick, it does not mean they will be.