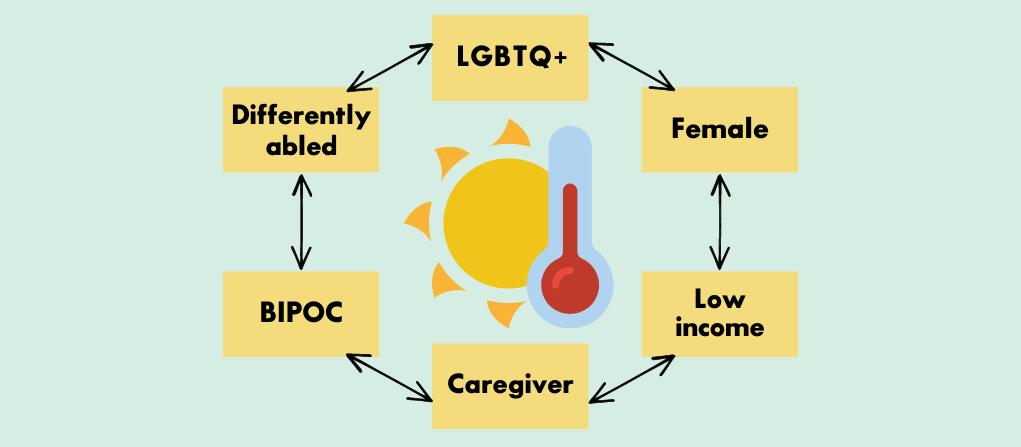

A diagram highlighting the intersectional impacts of climate change. Source: Yale Sustainability

There is a long history of minorities being excluded from the environmental movement – from prohibition from outdoor spaces to being left out of environmental decision-making. A clean, healthy, and sustainable environment are human rights for all, and this long-standing exclusion has negative ramifications on how fairly ‘green’ transitions occurs.

Starting in the 1890s, the environmental movement emerged from the progressive era’s conservation movement. Leading naturalists and advocates, such as Henry David Thoreau and John Muir, encouraged wealthy, elite white males to revere nature and embrace outdoor pursuits. The environmental movement focused on preservationist issues by romanticizing outdoor spaces and conceptualizing the “environment” as wild or pristine spaces for recreational activities.

Around the same period, and expanding in the 1900s, concerns about unfair and hazardous working and housing conditions led rise to the labor movement and urban environmentalism. Urban green spaces became a focal point of environmental and political activism. While wilderness-oriented activist separated environmentalism from the working class and urban residents, urban park designers worked alongside the poor and built spaces where the middle-class and working poor interacted.

Urban and rural concerns were solidly linked in the 1960s, with the immense popularity of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), which exposed the negative ramifications of toxic chemicals. Her book advocated for the right to a safe environment with a focus on home and community, along with nature and wild spaces. In response, middle class whites moved to more pristine and less toxic areas, while using their power and legal challenges to control the integrity of their communities. Meanwhile, minority communities became the dumping grounds for unwanted, toxic land uses, such as hazardous waste sites. Research soon made it clear the connection between race, class, and the environment. Environmentalism became immersed in the mass social movements of the 1960s, such as the civil rights and antiwar movements, giving rise to the environmental justice movement.

In the 1980s, environmental organizations grew increasingly large and mainly challenged environmental issues through legal and policy channels. Instead of grassroot activism, these organizations began to lobby Congress and business, and built close ties to industries. As these organizations grew and expanded, however, they became bureaucratized, hierarchical, and distant from local concerns. Wildlife and wilderness protection still dominated the agenda, and white males dominated the top leadership positions.

Today, environmentalism increasingly recognizes that systems of power and oppression have implications on climate change vulnerabilities, such as food access or energy affordability. However, those involved with the environmental movement are still mostly white, despite the disproportionate environmental impacts on minority and low-income communities and public opinion polls that have demonstrated the higher levels of environmental concern among minorities compared to whites.

The lack of diversity in environmental organizations is an unsettling facet of the largely exclusionary nature of many organizations, who have historically left minority communities out of the conversation. In 1972, the Sierra Club polled its members regarding whether the Club should “concern itself with the conservation problems of such special groups as the urban poor and ethnic minorities.” Forty percent of the respondents were strongly opposed to this, whereas only 15 percent were supportive. Attention to diversity matters has increased since then, but “diversity” gains have been from increased representation of white women.

Many avenues have the potential to increase minority participation in the environmental movement. In the forefront is the active inclusion of representatives from minority and low-income communities in the decision-making, design, and implementation processes of all environmental actions, from the grassroots level to the federal policy level. Many environmental organizations have active policies and practices that do not support inclusive cultures, but are working on developing transparent promotion processes, mentoring, and training programs in cultural competency which can help address the diversity problem.

Environmental history has largely excluded minorities and low-income communities, which impacts the way in which the environment is conceptualized. Access to a healthy living environment and to the outdoors are human rights, and the rapid onset of climate change impacts should add pressure to transition to a greener and more just world. Environmentalists need to ask what structural issues are preventing certain communities from being a part of this transition to put an end to a long history of environmental exclusion.