This month, researchers from the Stockholm Environment Institute, University of Gothenburg, University of Reading, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, University of Toronto, Technical University of Denmark and ETH Zurich assessed the impact of synthetic chemicals such as plastics on the stability of the Earth’s physical, chemical, and biological systems for the first time.

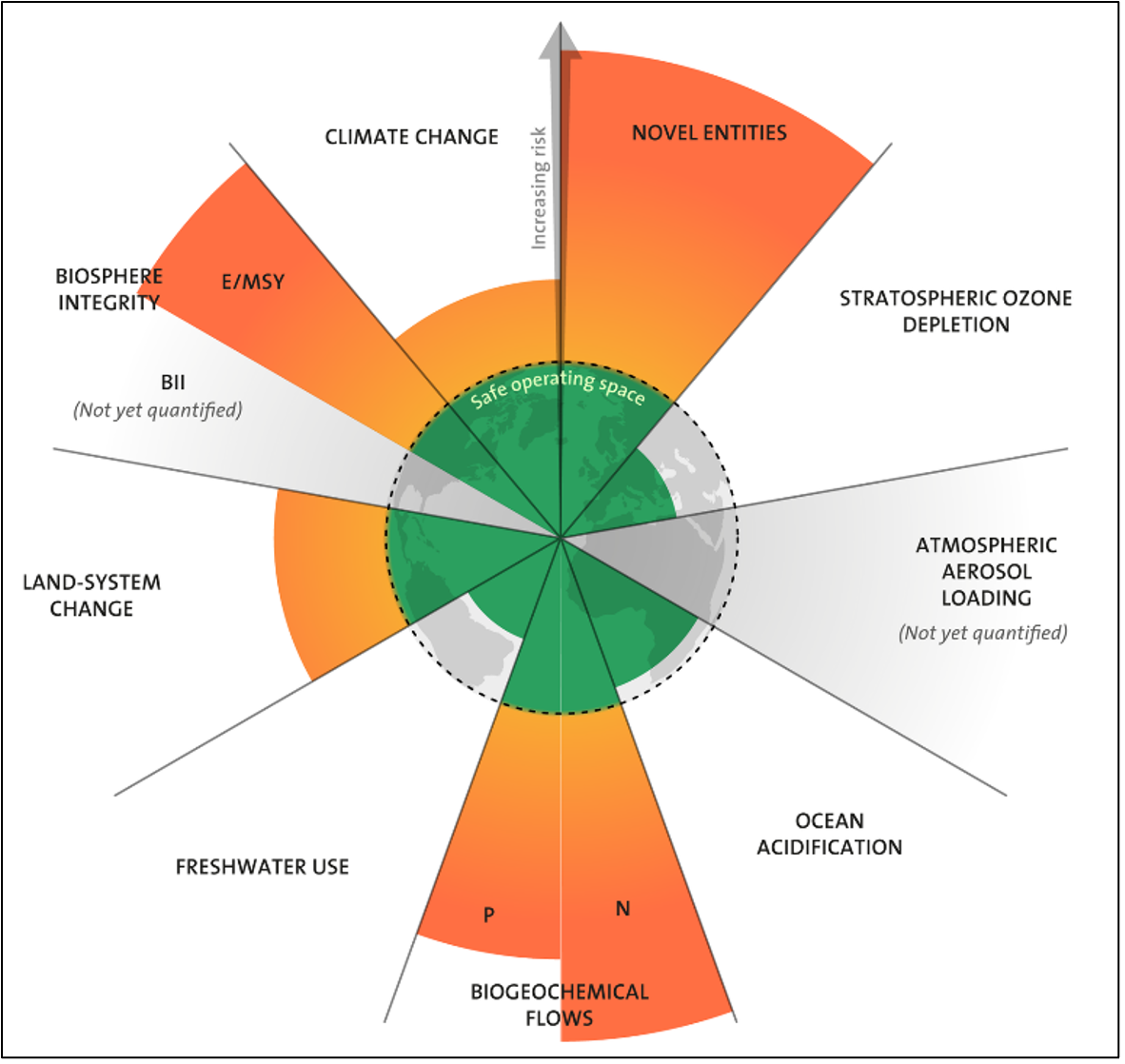

The nine planetary boundaries—which include climate change (i.e. greenhouse gas emissions and associated warming), the ozone layer, land-system change like deforestation or desertification, biosphere integrity (i.e. biodiversity loss), and freshwater use—were first identified in 2009 by a team of 28 international researchers. These nine boundaries are representative of the Earth system conditions—including land, ocean, and atmospheric processes as well as naturally occurring cycles like the carbon cycle and their many interactions—that have remained relatively stable over the course of the Holocene era (i.e. the last 10,000 years or so). Crossing any these boundaries increases the risk of abrupt and/or irreversible environmental changes (often called “tipping points”) like the melting of ice sheets or coral reef die off. In 2009, the researchers determined that three of the nine boundaries had been crossed—climate change, biodiversity loss, and biogeochemical flows (nitrogen and phosphorous, which are more commonly occurring than they would be naturally, largely because of fertilizer application). In 2015, the research was updated showing that four of the nine boundaries had been crossed—with land-system change added to the list.

Now, in 2022, researchers were finally able to quantify the impact of synthetic chemicals like plastics on Earth’s systems (called the “novel entities” boundary) and determined that this boundary, too, has been exceeded—five of nine planetary boundaries have been crossed (and one—atmospheric aerosol loading—has yet to be quantified). The researchers determined that chemical production has increased by a factor of 50 since 1950, and is anticipated to triple between now and 2050. Plastic production increased by nearly 80 percent between 2000 and 2015 alone. This drastic uptick in synthetic chemicals entering the environment outpaces our ability to understand and predict their risks—only a “tiny fraction” of the approximately 350,000 synthetic chemicals created to date have been analyzed to determine their health and safety risks. However, we do know that the risks of many synthetic chemicals are long-lasting and include increasing pollution, harming biodiversity and altering biogeochemical cycles (the processes by which essential chemical elements—like carbon, nitrogen or oxygen—are circulated within and among ecosystems).

Amid mounting evidence of the global scale and severity of chemical pollution, there are growing calls for governmental action: In 2021, more than 1,800 scientists from across the globe signed an open letter asking for the creation of a science-policy panel—similar to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—to address chemical pollution. Negotiations around a global treaty to combat plastic pollution are set to launch next month at the U.N. Environment Assembly. (In November 2021, the U.S. indicated it would support such a treaty.) If these negotiations are as successful as those that established the Montreal Protocol for hydrofluorocarbons from aerosols and effectively saved the ozone layer—there is reason for hope.