On April 4, 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the leading world body for the assessment of climate change—released a report called “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change”. The report provides an update on global progress regarding the reduction of greenhouse gases and other mitigation measures that are necessary to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change by limiting average global temperature increase to 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius (as globally agreed in the Paris Agreement).

Let’s start with the good. The report finds that we already have the technology we need and the know-how to reduce emissions in line with globally-agreed goals: stop burning fossil fuels, deploy renewable energy resources, enhance energy efficiency, electrify heating and transportation, and save more forests. The price of renewable energy has dropped dramatically: between 2010 and 2019, solar and battery costs fell by 85 percent while wind costs fell by 55 percent. The reason for continued fossil fuel production, importantly, is not demand: “people demand services and not primary energy and physical resources per se” (emphasis added), which leads to the amazing conclusion that demand-side strategies could reduce 50 to 80 percent of emissions across all sectors. Some countries are on the right track: at least 18 nations have reduced their total emissions every year for more than a decade. Some of those are making annual emission reductions large enough that—if all other nations followed suit—would be enough to reach globally-agreed average temperature increase goals.

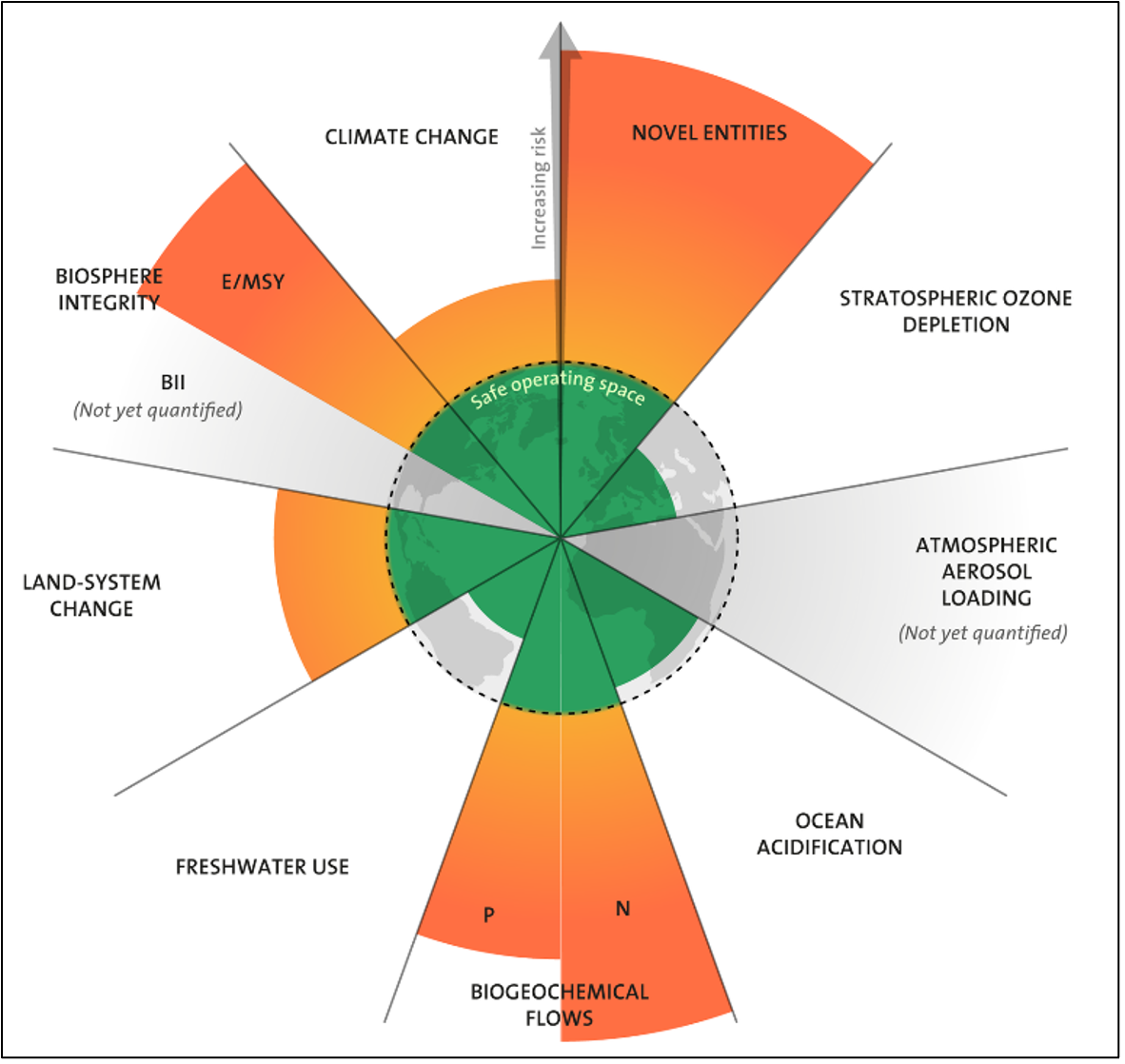

Image reproduced from: https://www.wri.org/insights/ipcc-report-2022-mitigation-climate-change

The not-so-good? The report finds that limiting global average temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius is very unlikely: after the highest global emissions in human history every year for the last ten years, global emissions would need to peak within the next three years (by 2025) and fall by 43 percent by 2030, which would be historically unprecedented. Even then, the IPCC says it is “almost inevitable” that the 1.5 degree warming threshold will be exceeded, at least temporarily. To have any chance of limiting average global temperature increase to 1.5 to 2 degrees, the report emphasizes the need to rapidly phase out fossil fuels: by 2050, coal use must decline by 95 percent, oil use by 60 percent, and gas use by 45 percent. That means some fossil fuel resources would be shut down prematurely—i.e., before the end of their intended lifespan—which also means there is zero headroom for new coal, oil, or gas resources. The conclusion that the only way to limit catastrophic climate change is to ensure that no new coal, oil or gas development takes place has also been reached by the International Energy Agency.

The report’s results are both sobering and uplifting: readily available, affordable technology across the economy can reduce emissions in line with what is needed to avoid catastrophic climate change, but we are headed in the wrong direction. Major political changes are necessary to right our course.